Iraq and Lebanon: Shared interests drive practical cooperation

Shafaq News/ When Lebanese President Joseph Aoun publicly ruled out integrating Hezbollah into the national army, many in the region saw it as a direct dismissal of the model adopted in Iraq with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). His words were sharp: “There will be no Popular Mobilization in Lebanon.” The statement, made in a sensitive regional climate, immediately stirred unease in Baghdad.

But the reaction wasn’t solely about the words. For many Iraqis, it touched a nerve, especially in a country where the PMF is not just a military entity but also a political force woven into the state’s post-ISIS security framework.

In Baghdad, the interpretation quickly tilted toward a perceived slight. Was Lebanon rejecting Iraq’s model as flawed or illegitimate?

Iraqi officials wasted no time. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoned Lebanon’s ambassador to Baghdad, demanding clarification. The response from Beirut came swiftly: President Aoun’s remarks had been misunderstood, and his comment was never meant to disparage Iraq’s path.

What

followed was a crucial phone call between Aoun and Iraqi Prime Minister

Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani, a gesture that helped clear the air. Both leaders

reaffirmed the strong bond between their nations and acknowledged the

complexities each country faces when it comes to balancing armed groups,

sovereignty, and foreign influence.

Parallel Pressures

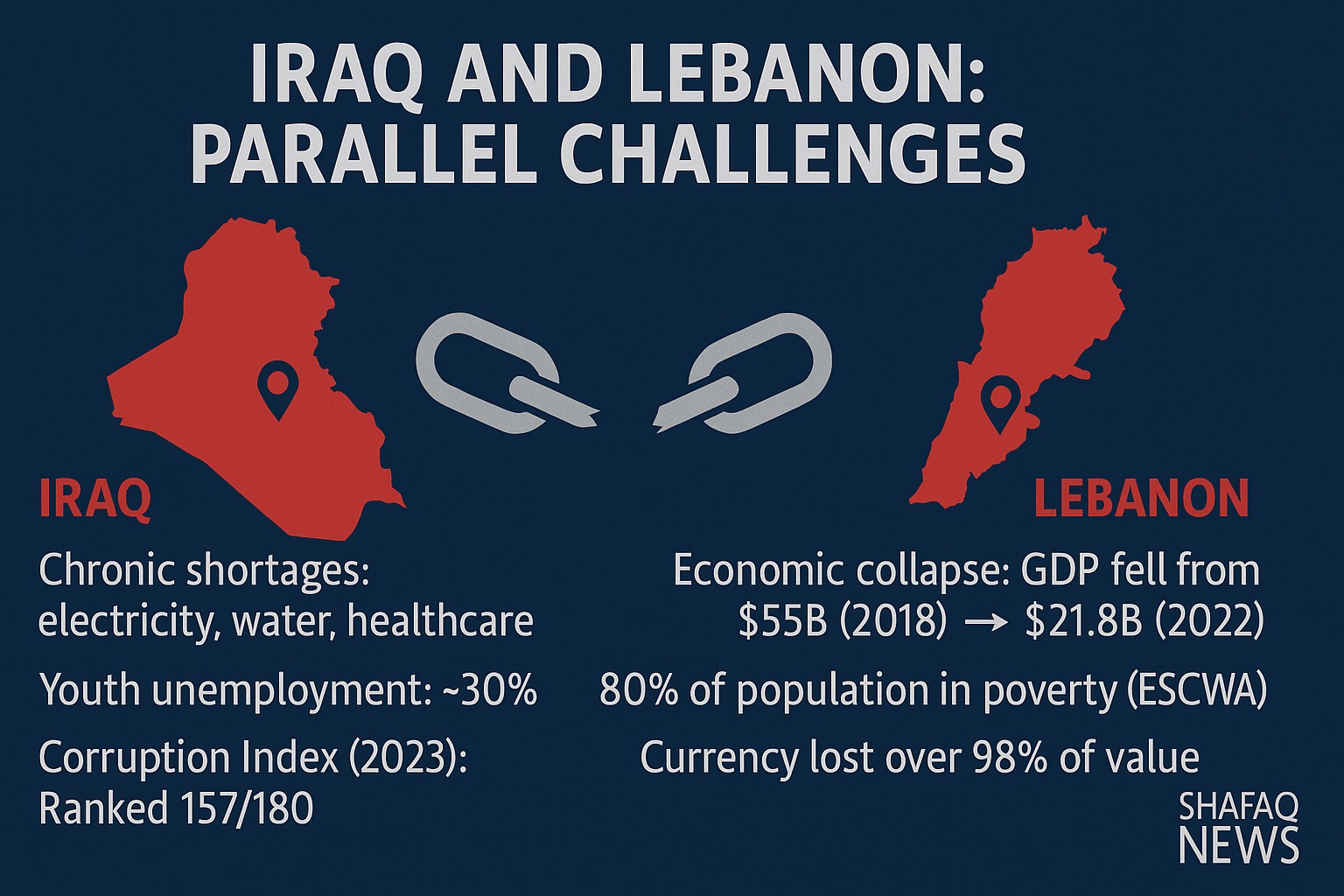

While a recent diplomatic incident between Iraq and Lebanon was swiftly resolved, the exchange brought into sharper focus long-standing political dilemmas in both countries. Beyond the headlines, Baghdad and Beirut remain under mounting international pressure to reduce the influence of powerful armed groups—Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) in Iraq—that have become deeply embedded in national politics and governance.

Western governments, particularly the United States, have urged both states to strengthen centralized authority and assert control over military forces operating outside formal security structures. Lebanese authorities continue to face demands to curtail Hezbollah’s military capabilities and reduce its regional activities. Similarly, the Iraqi government has come under sustained pressure to limit the PMF’s political reach and dismantle its “militia” structure.

However, disbanding or sidelining these groups is far from straightforward. Both Hezbollah and the PMF emerged during periods of institutional collapse and foreign intervention, positioning themselves as defenders of national sovereignty and community survival. Their legitimacy, in the eyes of many supporters, is rooted in their role during past crises rather than current political circumstances.

Hezbollah has gradually evolved from a resistance movement formed in the 1980s to a multifaceted organization with a significant social, economic, and political presence. In addition to its armed wing, the group operates hospitals, schools, and welfare programs that serve large segments of Lebanon’s Shiite population. A 2020 report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) underscored the broad reach of these services, which support tens of thousands of families annually.

The PMF’s trajectory has followed a similar pattern. Established in 2014 amid the threat posed by ISIS, the group initially acted as a volunteer force before being officially incorporated into the Iraqi state under Law No. 40 (2016). With an estimated 150,000 fighters, the PMF now holds sway not only in security affairs but also across border crossings, customs, construction, and trade-related sectors.

Their institutional roles, however, have generated growing scrutiny, particularly among younger populations disillusioned by persistent corruption and deteriorating public services. While Lebanon’s collapse has drawn more international attention, Iraq faces many of the same structural vulnerabilities.

Lebanon’s economic crisis remains one of the most severe globally in modern times. The World Bank has described the country’s financial collapse as among the worst since the 1850s. The Lebanese pound has lost over 98 percent of its value, GDP fell from more than $55 billion in 2018 to roughly $21.8 billion in 2022, and more than 80 percent of the population now lives in poverty, according to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). Emigration has accelerated, with waves of professionals, doctors, engineers, and teachers leaving the country.

Iraq, despite oil revenues surpassing $115 billion in 2022 and its status as OPEC’s second-largest producer, continues to face chronic shortages in electricity, clean water, and healthcare. Youth unemployment remains close to 30 percent, and widespread dissatisfaction persists. Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Iraq 157th out of 180 countries, assigning it a score of 23 out of 100. Although the country approved a record 198.9 trillion dinar ($153 billion) three-year budget in 2023 with significant allocations for infrastructure and public hiring, the risk of misappropriation remains high.

Public anger over political stagnation, sectarian governance, and economic hardship reached a boiling point in 2019. Mass protests swept both countries, with demonstrators demanding systemic reform and an end to elite impunity. In Beirut, rallies extended across regions, including traditionally pro-Hezbollah areas, challenging the party’s position within the ruling system. In Iraq, hundreds of thousands took to the streets, rejecting foreign interference, both Iranian and American, and calling for accountability. The chant “No to America, No to Iran” became a recurring slogan.

The Iraqi protests resulted in more than 600 deaths, with several incidents involving armed groups affiliated with the PMF. In Lebanon, the uprising prompted a wave of arrests, clashes, and media campaigns targeting activists. In both cases, the protest movements signaled a generational rift, led by youth who came of age in a post-conflict era but saw little improvement in governance or opportunity.

Since those protests, criticism of armed political actors has grown, particularly within civil society and independent media. A 2022 survey by the Al-Bayan Center in Baghdad revealed that 61 percent of respondents favored reducing the PMF’s influence in politics. In Lebanon, while public opinion polling is more fragmented, there has been a noticeable increase in criticism, even within regions where Hezbollah has long maintained support.

Both countries also face significant pressures from displacement. Lebanon hosts approximately 1.5 million Syrian refugees, making it the country with the highest number of refugees per capita worldwide. Iraq, meanwhile, continues to shelter more than 1.2 million internally displaced persons. These demographic pressures strain already fragile infrastructure and public services, compounding existing political and economic challenges.

International financial institutions have attempted to assist, but progress remains uneven. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has engaged with both countries, offering support in exchange for broad structural reforms. In Lebanon, however, negotiations with the IMF have repeatedly stalled due to resistance from entrenched political and financial interests. Proposed reforms have included exchange rate unification, financial sector restructuring, and a forensic audit of the Central Bank, a few of which have advanced.

Iraq’s

cooperation with the IMF has been more functional, and its recent budget

indicates a more proactive fiscal approach. Still, skepticism remains about

whether the state can implement its plans transparently and equitably. Critics

warn that without stronger oversight, large-scale allocations could be absorbed

by the same networks of patronage that sparked protests in the first place.

A Foundation of Cooperation

Beyond diplomatic headlines and political tensions, Iraq and Lebanon have, over the past fifteen years, steadily cultivated a partnership marked by pragmatic cooperation and mutual benefit. Their collaboration has grown across key sectors, energy, health, education, and culture, offering both countries lifelines during times of internal crisis.

Few gestures captured this spirit more vividly than Iraq’s emergency fuel deliveries to Lebanon between 2021 and 2024. With Beirut’s power stations barely operational and nationwide blackouts becoming the norm, Baghdad stepped in with over 600,000 tons of heavy fuel oil. These shipments kept hospitals, water stations, and public infrastructure from grinding to a halt, offering a temporary yet vital cushion to Lebanon’s deteriorating power grid.

But this assistance wasn’t offered for free. Lebanon responded with an oil-for-service arrangement, a workaround designed to bypass its dollar shortage while drawing on its professional expertise. Under this deal, Lebanese doctors, technicians, and engineers provided services in Iraq’s medical and technical sectors. The formula was unconventional but effective, and it established a framework of reciprocal support rooted in real-world needs.

In Iraqi hospitals, Lebanese medical missions have brought not only skilled hands but also strategic insight. Specialists in oncology, cardiovascular surgery, and critical care have helped treat complex cases, train Iraqi teams, and introduce new protocols.

Between 2021 and 2025 alone, more than 52 delegations of Lebanese medical professionals visited hospitals in Baghdad, Najaf, Basra, and Erbil. Many helped launch surgical programs that continued after their departure.

The health sector collaboration deepened during the COVID-19 pandemic when both countries faced severe pressure on their healthcare systems. Joint humanitarian initiatives emerged: mobile oxygen units were dispatched, PPE was coordinated between Red Crescent branches, and field clinics were established in underserved Iraqi areas. These efforts didn’t just address urgent needs—they laid the groundwork for sustained medical cooperation in telemedicine and infectious disease response.

Meanwhile, educational links have flourished quietly but significantly. Each year, more than 1,500 Iraqi students travel to Lebanon for university studies. Institutions like the American University of Beirut, Lebanese University, and Beirut Arab University draw Iraqis interested in medicine, engineering, international affairs, and law. Lebanese universities, prized for their multilingual programs and academic rigor, have become regional hubs for higher education.

Those academic ties extend beyond the classroom. Faculty exchange programs, collaborative conferences, and joint research initiatives have created enduring bonds between professors and scholars. Lebanese institutions offer scholarships for Iraqi students, while Iraqi universities host Lebanese lecturers in guest capacities. These academic exchanges have been instrumental in forging long-term people-to-people connections that go well beyond institutional protocols.

Religious and cultural bonds, especially between the Shia communities of both countries, add another dimension to this relationship. The clerical establishment in Najaf has sustained decades-long relationships with Lebanese Shia scholars, marked by theological dialogue, educational exchange, and mutual visits. These ties have shaped both religious thought and social policy, influencing discourse across borders.

One of the most visible expressions of this connection emerges during al-Arbaeen. In 2024, more than 140,000 Lebanese pilgrims traveled to Iraq, according to the Border Crossings Authority. Their journey to Karbala, while deeply spiritual, also fuels economic activity in shrine cities. Hotels, transport companies, and food vendors in Najaf and Karbala rely heavily on this seasonal influx, which has grown steadily over the past decade.

In a region often defined by division and distrust, the evolving relationship between Iraq and Lebanon offers a rare example of pragmatic cooperation grounded in shared hardship and mutual respect. While political tensions may flare, the foundation of their partnership runs deeper, built not on rhetoric but on tangible acts of solidarity and collaboration.