It is now widely accepted that climate change is a reality and human actions have, over the decades, contributed through our greenhouse gas emissions. All good science points towards catastrophic impacts if not contained. The rising frequency and intensity of extreme heat, flood, wind and other events continue to affect the health and wellbeing of all inhabitants of the planet.

This is a global issue and will require a global response, and though countries like Australia are now taking leadership in driving change, it is not comprehensive enough to keep the temperature rise within 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report 2024 highlights that, to stay on track towards a 1.5 degrees Celsius goal, the world needs to reduce emissions by over 50 percent by 2035.1 This may be close to impossible now given emissions and temperature rises to date. All sectors of the economy will have to work collaboratively to contribute to reductions and, without such sector-wide engagement, we will not succeed.

The built-environment sector is very well placed to lead this collaboration, as it draws from all sectors in the delivery of human settlements. The sector’s actions have implications on all three scopes of emissions, ranging from on-site actions (scope 1) to off-site electricity generation (scope 2) and off-site material and other production (scope 3) including urban design and planning.

To support this, the UNEP-hosted Global Alliance for Building and Construction (GlobalABC), with the International Energy Agency, created the “Roadmap for Buildings and Construction: Towards a net-zero-emission, efficient and resilient building and construction sector.”2 This reports that to deliver zero-emission and resilient buildings by 2050, a concerted effort is needed in all our areas of influence.

While there is increasing evidence of action to reduce emissions in the built-environment sector, the challenge is compounded by rapid global urbanisation and the immense rate of construction and development to cater for growing populations.

Navigating roadmaps to net-zero carbon

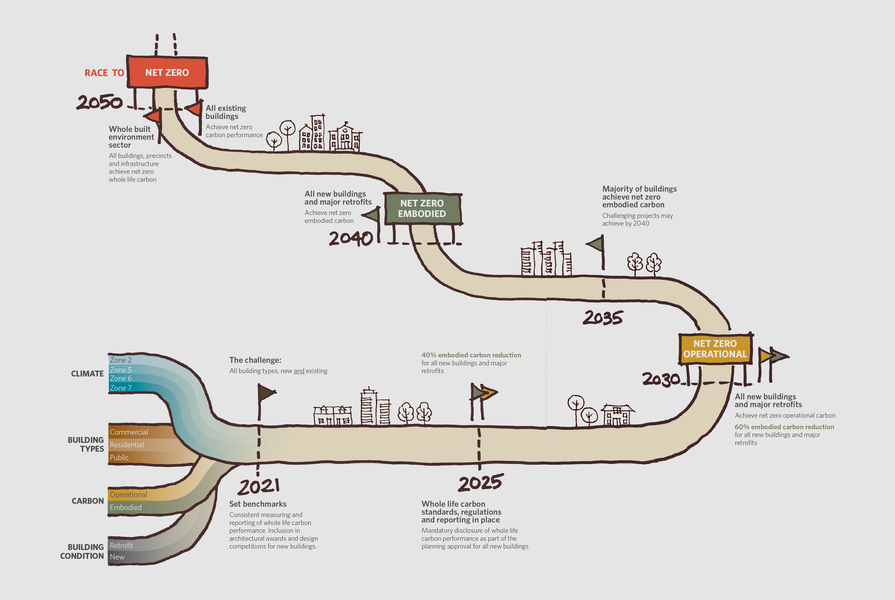

The international, multi-agency GlobalABC report provides an overview we can benchmark against. Locally, the Climate Change Authority (CCA) recently launched its six-sector “Sector Pathways Review” study focusing on 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius temperature rise scenarios and identifying decarbonisation contributions and opportunities in each area.3 The rigorous modelling of the “Built Environment” sector review highlights potentially rapid decarbonisation pathways by looking into how to best split the scope and responsibility for action among stakeholders. In another approach, the University of New South Wales’s 2021 “Race to Net Zero Carbon” guide highlights the responsibility of designers to advocate for different up-front options that would minimise building-related emissions, especially related to embodied carbon.4

What is most important is that Australia’s built-environment sector leads in emissions reduction, as it is well placed to do. Various roadmaps, pathway studies and plans have been conducted by stakeholder groups like the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA), the Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council, NABERS and the Australian Institute of Architects, and these suggest positive outcomes across a wide number of strategies, including higher levels of stringency of the National Construction Code (NCC), support for more on-site generation, a massive building of capacity, and the standardising of measurements and tools across the sector.

Similarly, the GlobalABC’s roadmap identifies key actions to support decarbonisation of new and existing buildings: national roadmaps and strategies to set priorities for the sector; standards and codes to gradually drive-up performance; regulatory frameworks to facilitate integrated action; narratives and engagement to drive demand; and capacity building.

Whole-of-life and whole-of-building

Historically, a lot of effort has been put into the energy efficiency of buildings, targeting their operational life and passive solar designs including facades and appliances. Life-cycle assessments have been around as a methodology but largely unused in practice until recently. Now it is evident that the building sector needs to take a whole-of-life and whole-of-building approach, which is rapidly coming into application. The GBCA points out that, without changing from business as usual, embodied carbon will make up 85 percent of built-environment emissions by 2050. So while material production takes place off-site, it needs serious consideration. The focus is also beyond current material life, and circularity in design is being adopted – though not as much as required to meet net-zero carbon goals.

The link between circularity and decarbonisation is very strong, with recycled and reused materials having much lower embodied carbon. Figure 1, drawn from the “Race to Net Zero Carbon” guide, highlights the range of considerations needed beyond only the front-end of building life.

Top-down and bottom-up approaches

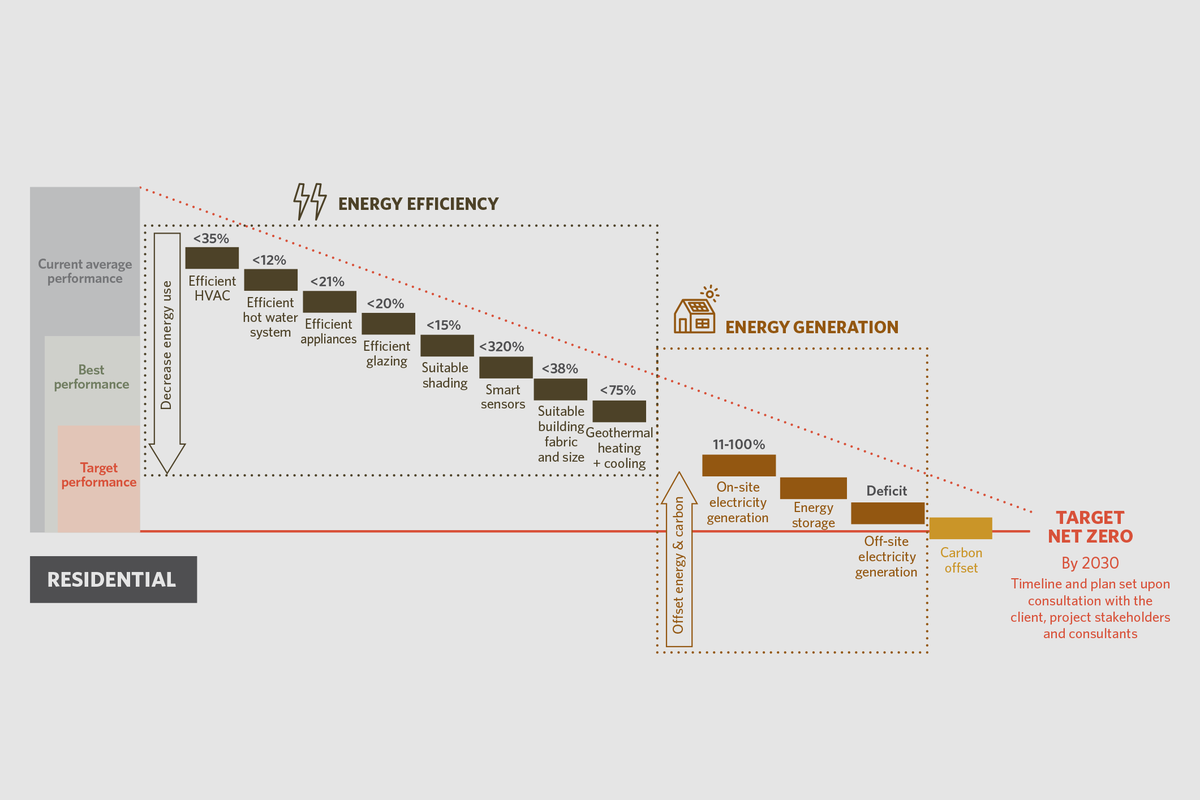

We are familiar with the bottom-up approach – what we can do to minimise energy use through good design and system and appliance integration. This includes material choices to minimise embodied carbon upfront and over a building’s life. Top-down factors like how green the grid is are mostly driven by other influences. The national electricity grid now has around 40 percent renewables and is predicted to grow to around 70 percent by 2030. The increases in rooftop and large-scale, off-site solar and wind power are major contributors to this. Resources like Open Electricity, which draws live data from the National Electricity Market, can be accessed daily to verify carbon intensity in energy supply.5 Some states, such as South Australia, have a much higher proportion due to their mix of generation fuels.

In terms of the supply chain, the NSW Decarbonisation Innovation Hub is leading the way in finding new energy sources. Just over the horizon, sources like green hydrogen may play a major role in the manufacturing sector to bring down embodied carbon.

As the carbon intensity of the grid improves, driven by renewables displacing coal, the role of gas will change too. Gas is more carbon intensive than renewables, and has been linked to significant health impacts, so it makes good sense to avoid locking in our dependence on it. Electrifying all buildings is an essential part of the urgent journey to net-zero carbon emissions.

So, what is needed?

A 2019 study by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water projects that the built-environment sector could reduce emissions by 69 percent (compared to 2005 levels) by 2030.6 A granular look at different building types (new and existing) and different climates shows net-zero carbon can be reached for most new buildings by 2030 by using a threefold methodology: demand minimisation (involving high energy efficiency and good passive design), use of on-site energy generation and use of off-site renewables.7 The approaches for different buildings vary, with cost influencing the first two and grid access (main or local) affecting the third. The fundamentals are basic, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Placing these in a pathway, such as in Figure 4, creates a feasible strategy.

It is evident that the technology and systems required for these improvements will continue to be developed. We already have a very strong capability for delivering high-performing buildings, but only a relatively small proportion of architects and engineers seem to be leading the charge. Hence, the case for stronger narratives and capability is well justified, and linking professional fees and awards criteria to measured performance may help.

Ultimately, good design should look for new solutions or even new paradigms for delivering a net-zero carbon, resilient, healthy, circular and regenerative built environment. Design professionals need to go beyond the single-metric approach. Factors such as biodiversity loss are significant and require serious consideration on every site, and while cost will always be important, so too will be costing the true benefits and returns, as is finding better ways to deal with split incentives. We must understand that while the end ambition is important, how we navigate the transition is what will help us deliver net-zero carbon goals.

— Scientia Professor Deo Prasad AO FTSE is an internationally recognised expert in the field of environment and sustain-ability with a focus on net-zero carbon innovations.

1. “Emissions Gap Report 2024: No more hot air … please!” United Nations Environment Programme, 2024, unep.org/ resources/emissions-gapareport-2024

2. “GlobalABC Roadmap for Buildings and Construction 2020–2050,” GlobalABC, 2020, globalabc.org/climate-action-roadmaps-buildings-and-construction

3. “Sector Pathways Review: Built Environment,” Climate Change Authority, 2024, climatechangeauthority.gov.au/sites/default/ files/documents/2024-09/2024SectorPathwaysReviewBuilt %20Environment.pdf

4. Deo Prasad, et al., “Race to Net Zero Carbon: A Climate Emergency Guide for New and Existing Buildings in Australia,” Low Carbon Institute, 2021, unsw.edu.au/content/dam/pdfs/unsw-adobe-websites/arts-design-architecture/built-environment/net- zero-guide/2023-01-13-Net-Zero-guide-online-version.pdf

5. Open Electricity: explore.openelectricity.org.au

6. “Achieving Low Energy Existing Commercial Buildings in Australia,” Ernst & Young, 2019, dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/achieving-low-energy-existing-commercial-buildings-in-australia-final-report.pdf

7. Deo Prasad, et al., Delivering on the Climate Emergency: Towards a Net Zero Carbon Built Environment (Springer Nature, 2022)

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Apr 2025

Words:

Deo Prasad

Images:

Illustration by Sara Jinga

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2025